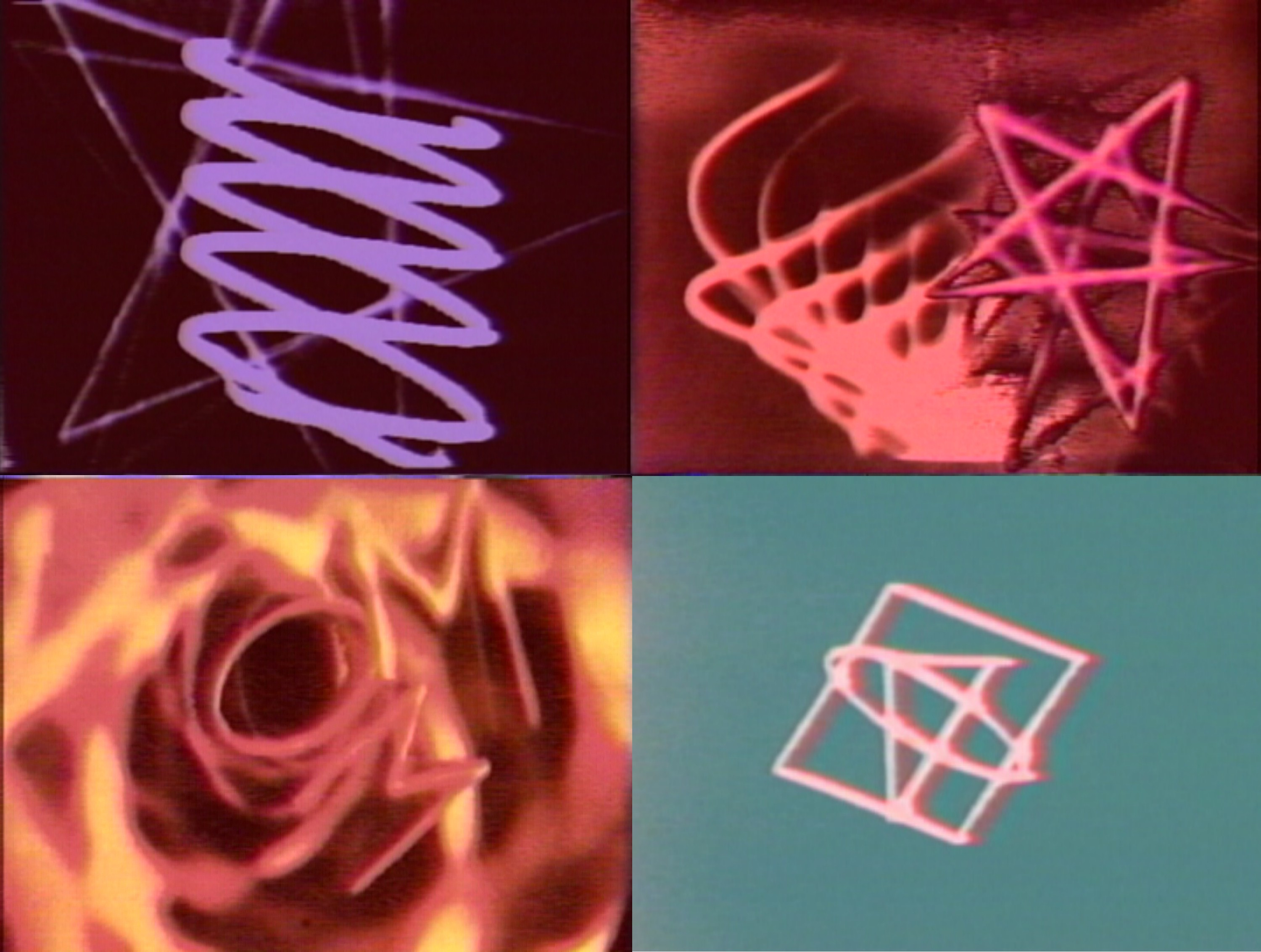

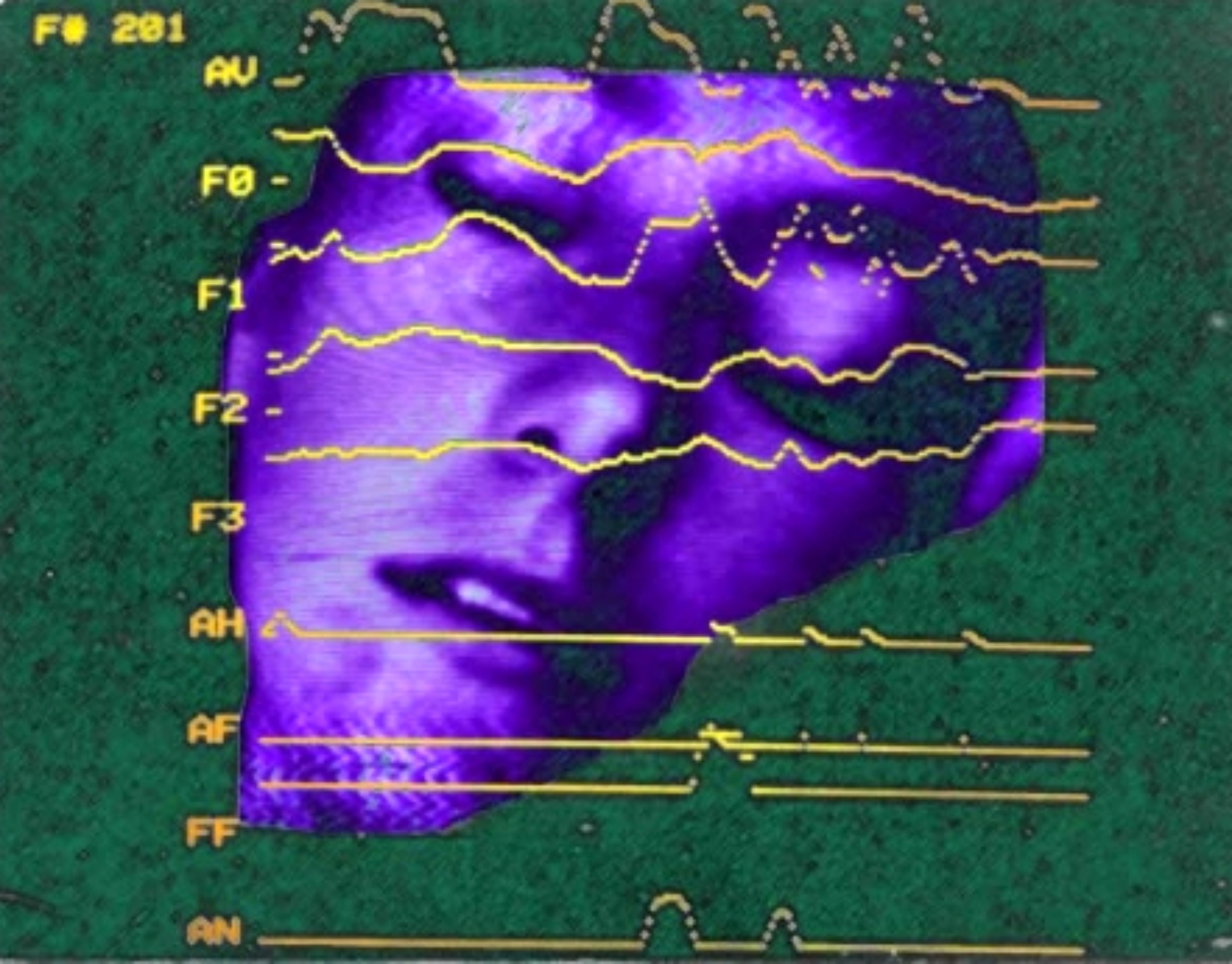

Fig. 1: Two frames of the rotating Boomerang produced for Mick Glasheen's Uluru using Doug Richardson's Visual Piano PDP-8 computer

graphics system. [Courtesy: Mick Glasheen]

The origins of Bush Video

After the shoot at Mimili and Uluru Glasheen returned to Sydney. He comments:

“I remember coming back from Central Australia. That was the second time to Central Australia then, when I went with Fat Jack and the video.

“Came back, and then I heard about this building in Broadway that Johnny Bourke owned. This is the brother of Lindsay Bourke. They seemed to have a big huge place upstairs that looked like a good place to live and to edit my videos. And there was space to put a Dome on the roof. So I re-met Lindsay’s brother John, who I’d known doing Architecture. He wasn’t really a close friend, but I always had a good relationship with him in Architecture. He had by that time finished Architecture, was an architect, and was working as a real estate agent really, and was buying up half of Glebe Point Road. [At] that time he was somehow in a position where he was buying an incredible amount of properties and developing them. Painting them yellow.

“He had this building in Broadway, a six storey building [actually a warehouse building at 31 Bay St, Ultimo in Sydney] which he re-named Fuetron, which was the name of this furniture company that he had. He was selling enamelled pine-board minimalist designed furniture downstairs on the first floor, and all the upstairs were empty and his brother Lindsay [a hippie musician who played synthesisers and an electric organ] was then going to have an art studio on the top floor. And Johnny and I worked out that I could have the fourth floor under Lindsay and use the roof.”[1]

The Fuetron building was a warehouse building at 31 Bay St, Ultimo. Mick’s space was the vacant fourth floor of the building. He moved into to set up his studio so he could begin editing the material he had shot at Uluru into his intended film about the “mythic science” of the aboriginal dreaming stories [tjukurrpa] of this sacred site.[2] John Bourke’s brother Lindsay Bourke, a hippie musician who played synthesisers and electric organs, lived on the fifth floor, above Mick.

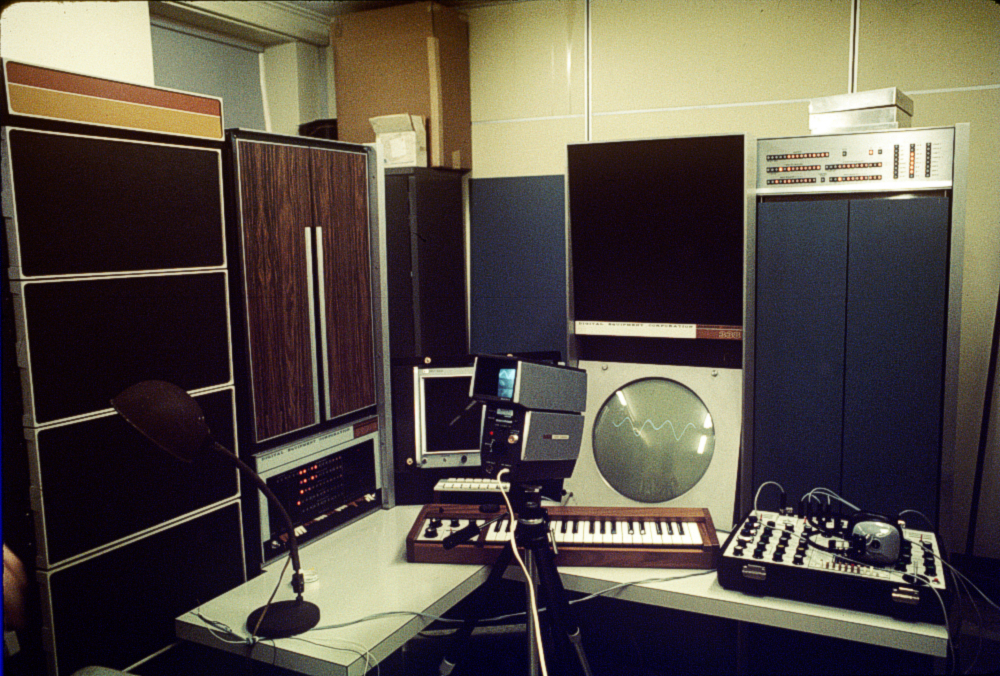

Having found a studio space near the University of Sydney, Mick then discovered the experimental computer graphics facility that Doug Richardson had established there, and it was just across the park from Bay St. Mick commented that they were quite welcoming.[3] The graphics system had been developed by Richardson on a DEC PDP-8 mini-computer [4] with a vector-graphics DEC 338 Display and was housed in the first floor of the Physics building. [A vector-graphics system draws lines from one specified co-ordinate to another. It is not a raster (i.e., TV-based) system, but more like an oscilloscope.] Richardson called his vector graphics [5] application software the Visual Piano. Graphic output was displayed on a large circular radar type screen known as the DEC Display 8 which had a drawing resolution of 1024 x 1024 dots.

The facility had been established through the collegial generosity of John Bennett, the then head of the University of Sydney Computer Science Department. It was made available to Computer Science students and to artists - including Gillian Haddley, Frank Eidlitz and Bush Video - whom Richardson invited to come and use his experimental graphics facility. Among them they produced a great variety of computer images for film, graphic design and video.

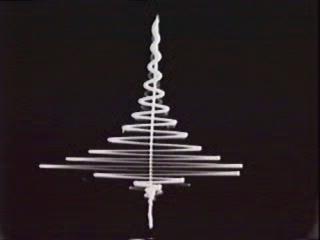

Mick got to doodle around a bit on the PDP-8 system, drawing 3D objects. He was intrigued by the persistence of the image on the 338 Display screen and shot 16mm film of it, wanting to use 3D images in his films. An example is the “Magic Boomerang” that was used in Uluru.[6] It starts as a 2D object spinning around and moving through 3D space.[7] It spins about its centre, as a boomerang does [Fig.1], while flying around the screen in a larger loop probably under the control of a sine-wave from a waveform generator (read: sound synthesiser) that could be fed to the computer through an analogue-to-digital converter attached to the PDP-8 as a peripheral. It then grows into an animation of the flight of a boomerang intended for Glasheen’s film Uluru [8] [Fig.2].

As always, there are bugs in experimental electronic systems and the PDP-8 was prone to them. One of the bugs was that with objects rotated about a centre there tended to be a line from that centre of rotation to the object as though it were on a fishing line. You can see this in the frames of the boomerang in Fig.7. It was later in 1973 (after Nimbin) that Richardson came over to the Bush Video studio and announced that he had the boomerang on the screen, so bring the camera. The boomerang was flying around the screen looping the loop and leaving the persistence trail “carving 3D space”, and it was finally running without the “fishing line tied to it”. [9]

Richardson’s system was used to produce a range of computer images that were used by Bush Video in several of their projects including Metavideo Programming, which we will come to below.

But a larger development followed.

Over the next few months Mick’s studio in the Fuetron building was the site of the initiative that developed into the first functioning (albeit experimental) video access centre in Australia. This was the Nimbin Communications Centre, established for the Aquarius Festival at Nimbin in May 1973 under the auspices of the Australian Union of Students.

Nimbin Communications Centre

In late 1972 and early 1973 Johnny Allen and Graeme Dunstan, both graduates of the University of NSW, and now working as cultural officers for the Aquarius Foundation, the cultural arm of the Australian Union of Students had been travelling to all the universities in Australia to enthuse students about the Aquarius Arts Festival due to be held in Nimbin, northern NSW, in May 1973, of which they were co-directors. Among their plans was that they should make a film of the Festival and they intended to apply for funds from the Experimental Film Fund of the Australian Council for the Arts to do this. This led to the proposal that they set up a video co-operative as one of the projects for the festival and that, in turn, led to the establishment of the Nimbin Communications Centre at the Aquarius Festival at Nimbin.

Glasheen describes how the project started.

“Well the initiative came from the Aquarius Festival organisers Johnny Allen and Graeme Dunstan, yeah, to actually do a video documentation of the coming Aquarius Festival, and to set up something… you know to set up some closed circuit...

“And at that time, I remember I was in the Fuetron building one morning when Johnny Allen and Graeme Dunstan came around talking about the Aquarius Festival that they were organising. This was in early 1973. I was looking at Uluru, looking at video tapes that I got with the half-inch Sony stuff. And that’s half the reason they came here, I suppose: here’s a person working with video. So I was looking at these half-inch videos and also I was looking at 16mm film. And that’s what I was doing, I thought I was finishing Uluru. Then the whole Aquarius festival totally interrupted, [and Uluru was] thrown out till 1977. So that’s like four or five years. But that’s happened all the way through. Everything I’ve ever done has always taken about seven years. It’s a seven year cycle.

“Johnny [Allen] had been appointed cultural director at NSW Uni and I’d worked with Johnny a couple of times prior. I was working on something at uni, Advertisements for the Future, and doing some computer graphics [for that] at that time with Doug Richardson on the IMLAC [10]. Anyway Johnny and Graeme came around and they were saying “we’re going to have this Aquarius Arts Festival and we’re thinking of applying to the Film, Radio and Television Board for funding to set up a video cooperative”. And also Johnny was talking about making a film of the whole festival. So there were these two things: a film was going to be made and would I be interested in shooting some of the film and also helping set up the video.”

“And I thought both of the ideas were terrific and the film was going to be like a... There was some film had been made where six independent filmmakers gave their versions of an event that they went to and they filmed it and that’s what he was thinking of doing, having about six people, giving them all film and let them shoot their own version and editing it all together. And that would have been great if that happened. Like, the Nimbin festival needed some fantastic documentation like that. It never had it in the end, we never recorded it properly. And I remember going up to Nimbin after that. There was going to be a meeting up in Nimbin about what the Festival was going to be, what different people could do.” [11]

Johnny Allen also visited Joe Correy [aka Joseph El Khouri] and Melinda Brown, both then in Melbourne, and Annie Kelley (from Adelaide). Joseph had been inspired to make films while running the Film Society at the University of New England and had subsequently joined up with filmmaker Bert Deling and acted in his film Dalmas. Johnny Allen wanted to discuss making a film of the Festival and invited them to get involved in the video communications centre project at Nimbin. They were then joined by Anna Soares, a visitor from Chile [or Portugal ??] and John Kirk who had returned from working with TVX in England [See Chapter ??]. This group of people, along with the photographer Jonny Lewis – who had been a resident of the Yellow House – Mick's architect friend Tom Barber, and Fat Jack formed the collective that set up the video centre in Nimbin and who later became Bush Video.

Ultimately it was Johnny Allen and the growing collection of media and video activists, architects, technicians and film-makers that assembled around the idea of both the festival and the communications centre proposal that led to the Nimbin Communications Centre which, in turn, led to Bush Video.

While the starting point for the AUS had been to document the festival, there turned out to be more interest in setting up a video co-operative that might provide a space in which to develop ideas that could lead to a democratic and accountable media. This was partly initiated by a Canadian visitor, David Weston, who suggested to the festival directors that they could set up a media centre to be operated within the festival township [12] and organised along the lines of the Canadian Natonal Film Board's Challenge for Change project [see Chapter 1], which also later became the model for the Video Access network.[13] There had already been some discussion around the idea of a video access centre led by John Hughes with his 1973 proposal for a “Video Exchange” in Melbourne (See Chapter 8). Much of the interest in community use of video was based on the appearance of Michael Shamberg's Guerilla Television [14] and the journal Radical Software [15], both issuing from the U.S.

Johnny Allen had also written to “Hoppy” Hopkins in the UK about the project and this led to John Kirk's return to Australia to become involved with it. Over the weekend of 17-18 February, 1973, a meeting was held at Nimbin to discuss arrangements for setting up the infrastructure for the festival. Glasheen, El Khouri and Melinda Brown were present, however Weston was unable to stay for the Festival and after the initial planning meeting it fell to El Khouri and Glasheen to organise the media centre.

While Joseph adds

“And Bauxhau and Mick and Johnny Allen, Graham Dunstan, Col James, Melinda and I and a whole lot of other people, all went up. We met in houses in Balmain and somehow there was going to be this meeting up in Nimbin.

“Colin James chose the place. He chose Nimbin, and told Johnny. And Johnny was working out of this place in Carlton, AUS headquarters, but he was all over the place. He was going... flying to India, and places, Bauls of Bengal. He and Baxhau had arranged for the Jazz Pianist Dollar Brand to come” [16]

Glasheen remembers

“going up with John Voce [17] and Clive Joy [???]. Taking the video up even, to record the meeting. And we had a meeting in the Town Hall and we talked about: yes, apply to the Film Radio and Television Board for funding and we’d apply as the Australian Union of Students who were putting on the festival, who were employing Johnny. So it was the Australian Union of Students who were applying for the money, but we were writing out the application. At that meeting... I remember coming up to Nimbin with two other people [Joseph El Khouri and Melinda Brown] who I’d met in Central Australia at the Inma that I went to with Fat Jack and I took video. I’d really only known about it through Baxhau, whom I’d met earlier and he was helping organise [it] with the Arts Council: Doctor Coombs, Jenny Isaacs, and it was one of the first Arts Council funded big aboriginal cultural events. And I crashed that really, with Fat Jack [who] did a hell of a lot of good work there: setting things up, and I shot a lot of video there, built a communications centre with a big spinifex dome. But two other people were there: Joseph El Khouri and Melinda Brown. [They] came, because they’d visited me in the Fuetron building, after I’d met them at the Inma.” [18]

Joseph continues

“First we went to Nimbin for the original meeting, and there was this guy, a Canadian guy [David Weston], who was organising video, and they were all talking about this Challenge for Change thing, a kind of community-based video. I didn’t know much about it, but I know it was a kind of community-based use of Video – and this guy was supposed to be organising the video element of the Student Festival.

“And then, after this meeting, we checked out Nimbin, the town, and we had a meeting in the hall there, and it was all very interesting. And Mick and I decided to become involved, and there were a whole lot of filmmakers there: Brendon Stretch was one, I remember. And that guy [Andy Trenouth] who was involved with you in the videos, who managed the theatre [the Chauvel cinema].

“Yeah, so we're all up in Nimbin and we had these meetings, and the filmmakers were there, going to do their film, and Mick and I decided to get involved in the video side of things. As I said, there was this Canadian guy organising it.

“And then we all came back to Sydney, and Melinda and I were living in Bondi. And then we went and saw Mick at the Fuetron Building that belonged to Lindsay’s brother. And Mick and Lindsay were there. They each had a floor. Lindsay was doing his exhibitions and Mick was staying there. And Johnny Allen came and told me that this guy who was supposed to be organising the grant had gone back to Canada, because someone had died.

“And I said: “Well, I’ll do it”, because I’d already applied for... I was used to the AFI because had I got my grant and I already knew the process, and I was always going in and out of the AFI, it was so close. So they all knew me there and whatever. And because I had the experience of organising stuff with Bert and putting in applications and whatever.”[19]

According to Glasheen, he and el Khouri then wrote an pplication to the AUS for funding to establish a model community access centre.

“So, it worked out that both Joseph and I then worked out what we needed to do the video documentation, and I was like... we needed three portable videos and a studio camera and lights, you know... whatever. And it was quite a big comprehensive package. I remember it was no more than fifteen thousand dollars, it was about $15,000. But we did get, I think it was at least three or maybe four portable videos, all National. Like we really studied what to get, whether we were going to get National or Sony, and we got National. And we reckoned they were superior and we [also] got, you know, a mains deck and we got a studio camera and lights and we built our own dollies and we also had budget to actually [buy] food for twenty people for two months or whatever, and electricity … and bought lots of old second hand television sets as well. We needed all these television sets as monitors to put up into the township of Nimbin to actually broadcast out what was happening from Bush video’s studio. Like we didn’t have any real idea of what...” [20]

Joseph then had it typed out and sent to AUS. As he puts it:

“Then I went out with Graham to the University of New South Wales, and wrote the application out and Robyn Archer was helping, she was the cultural manager out there. So I’d give the application to her and she’d take it to the girls in the office, and get it all typed out. Anyway, got the whole thing typed up, handed it in, then Melinda and I went back to Melbourne. And we were all waiting for the decision – this is between February and May. And there in Melbourne we hear: It’s okay, we got the grant. So come back to Sydney. But I mean, the whole thing takes weeks to go through. We come back to Sydney and I remember ending up [spending] Easter with Jonny, Jonny Lewis, who was living at Albie's, who I’d finally met when he organised that original independent filmmakers’ festival where we showed our movies I was talking about.” [21]

AUS had, in turn, applied to the FTB's predecessor, the Interim Council for a Film and Television School [or was it the Experimental Film and Television Fund ??] for “support for the video experiments at Nimbin in May with a grant to Aquarius (the cultural arm of Australia Union of Students) of $15,000 for the 10 day festival.” [22] With this funding Glasheen and el Khouri purchased 3 National ½-inch portapaks, a Shibaden ½-inch VTR (what was known as a “bench deck”), a small studio camera, lights, video tapes, a van with which they could move all the equipment and enough coaxial video cable to cable up the township and the main areas of the Festival. [23]

The main activity of the project became to introduce interested festival-goers to video so that they could go out and record festival events and then broadcast these out around Nimbin and the festival site through a collection of second-hand TV sets that they had also bought. [24] The sets were placed in the main sites of the festival, e.g, the Rainbow Café which managed to feed a large percentage of the students who came to Nimbin for the festival.

According to Glasheen,

“Bush Video was formed for the Aquarius Festival. It was totally just brought together to do that. And then a lot of people came together, in those two months of when we were getting the equipment together. A lot of people just gathered around Fuetron, they heard that there was going to be this great festival on and there was this place, Fuetron, where you could come and ... people would kind of squat there. So I remember Jonny Lewis arrived, and he was excited, with his girlfriend Annie. And then John Kirk arrived, and he’d just arrived from England and he’d heard about it in England. Johnny Allen had actually sent some communication off to John Hopkins, about doing this video thing… So John Kirk came on that. And other people who were friends of mine, like Tom Barber and Jack Meyer and Fat Jack, the people who had helped me build intervalometers and do experimental film things, they were around too, and they joined in. So it was this amalgamation of old contacts I had and new people.” [25]

John Kirk has told me that he arrived back in Australia at “ the beginning of ’73. March”, in time for the first meetings about setting the video up at Nimbin.

“I went to the Arts Council [the EFTF] in week one or week two, and they said: You need to go and meet these people, right. So then I was sitting with Mick and Joseph El Khouri, and Johnny Allen.

“So they kind of knew what they were doing, but Mick said: We’ve got to hire a truck to get all this cable up to the thing. And I said: Well, look at the economics of it. You can probably buy something for that sort of money. So they bought the Bush Video van. And at that stage they were looking at purchasing portapaks and those sort of things, and a switcher. And I knew enough to be able to tell them they needed vertical interval machines and they didn’t have a colour camera, but they could buy a colour switcher, right, with a chroma key on it, and all that sort of stuff.” [26]

Jonny Lewis describes how he became involved in the Nimbin project:

“I remember one particular day, I think I was with Annie Kelley, who was a great love of my life at one stage. We were over in Bay Street, and there was Mick. And I remember the day because it was... Mick takes his time in acquainting himself with people, or he did then. And I remember we were just in the yard. There was a yard next to the old Fuetron,

“And in the yard, there was a tin can and it was making this wonderful music, as it was blowing around the yard. And maybe you needed to be there to understand what I'm trying to say. But it was, the three [four ?] of us were just... there. And then of course, they started talking at further length. I think it was Mick, and Joseph, of course, was there...

“Anyway they started talking about Nimbin. And I knew nothing about Nimbin except that Bush Video was going to go up and represent itself by showing video tapes, and making them. I was very, very lucky and somehow I got myself up there and... I can't remember what vehicle I was driving. I think I had a little Renault, a little French car. I think my mother tried to help me out with that. But I was working as a labourer.” [27]

Joseph and Jonny took a portapak:

“up to Nimbin at Easter, and filmed the first Bush Video tape of Jonny and me and Annie [Kelly], and Linda Slutzkin, who became Albie’s wife. We got in a little “V-Dub” or something [probably actually Jonny's Renault] and the four of us we went up to Nimbin with the portapack and did this video.

“So Jonny and I and the two girls – went up there with the portapak, and we went up to the swimming hole – you know the place where they had a rope. It was like a little waterfall and they had this Tarzan rope, and you would swing out in space. And we did this videotape, Jonny and I did this video. It was really our first Bush Video tape. We were all naked and swinging out on this vine, or rope or something, and jumping off into the pool.

“And then we sent that back to Albie and he thought it was great. We used to watch it: This is great, just going out in the bush and shooting video; it’s so electric and it’s so bushy.

“Then we came back – because we knew we’d got the grant but the money hadn’t come through yet. So it had to take time, and it still hadn’t come through and we had to get a loan from the bank.

“I had to get this loan. I organised it. Because I was representing AUS and Johnny [Allen] it was okay. They were quite willing to give us $15,000. And so we could pay for the equipment. And I remember coming out of the bank with $2000 in cash, and I’d never had so much in my hand at one time.

“Then Mick and I started ordering the equipment. We decided to get one from Sony and two National Panasonic. And Annie Kelly used to drive me around, and she had a car and we’d go to all these places. And then I think it was Martin Fabinyi who found this old van out on Parramatta Road.

“He said: “You must come and check this out.” So we sent Fat Jack out, I think, to check it out. He said: “Yeah, it’s a beauty.” So I remember I went out there on Parramatta Road and bought the old van. It used to be used as a processing van by the Sydney Morning Herald, at the races. They had a dark-room in the back of it. So it was good. We knew we needed something to carry our equipment in, but this was great. We could use it as a camping van or whatever. I think it was $800. And Fat Jack took it out to that servicing place where you do it yourself.

“And Jonny and I were hanging out a lot together. And we were excited to be getting into video at last, getting some equipment that – because there were these people who had – I think Roger Foley had a portapack. – these quarter inch [Akai] ones. They were just starting to appear. We’d read about this stuff and been so excited by it, you could just shoot stuff without all the hassles, film production, and people saying: “You can’t do that; it has to be done this way”. So we were so excited by the concept, not realising all the hassles, the technical hassles we were going to get involved with; this half inch video, which was prematurely video, not like our little digital videos now.

“So Mick and I organised all this equipment, decided what we were going to buy: one colour, one studio camera, three portapaks. Because remember, we’ve got this agenda to do a kind of community video.” [28]

Mick adds:

“Like we’d formed about two months before the festival anyway... well the money had come through to get the equipment. And we were in the Fuetron building and we used to just unpack the equipment, we used to just go out... and these boxes would just come in... and we had money in the budget to buy a vehicle too, so we got that Bush Video van, which was a great asset, a great buy.” [29]

Joseph continues:

“Then John Kirk arrives, showed us this tape he’d done in London with Hoppy, telling us all about that. And he thought what we were doing was interesting, so he decided to get on board. Jonny and I had come back from Nimbin. Then we packed the van up with all this equipment. Mick had this dome but he didn’t have a skin. He said: “We need so much money; can we use it out of the budget?” Yeah, we got plenty …

“So that was the dome. We got the dome. Ken Beatty [aka Kenny Plosions] built the skin for it. This all happened really quickly because we just had to pack it all up, and head back to Nimbin. So this must’ve been after Easter, just early May. The festival was in May. We got up there and we had a terrific journey up there with John Kirk and Mick. I think we went in the van. Maybe Annie and Jonny went separately in her car. Then we had this one meeting where we came up with the name of Bush Video, so we put Bush Video on the side of the van. This was before it was painted silver – it was still its original colour.

“In a way, we were trying to explore all these experimental differences brought up by video. So what actually happens: we’re thinking about cable TV, community video, in other words involving the community, by showing stuff, but also getting them to shoot stuff.

“Because we set up this house in Nimbin during the festival, charge all these batteries and hand them out to people to go off and video whatever they want, at the same time as I used to go walking around with a video camera, shooting Abdullah Ibrahim [aka Dollar Brand] playing his piano, or just wandering around through all the activities, the yoga and all that, and videoing the sauna and all that sort of thing. I did a couple of good half hour videos, which would be interesting if they could be transferred, especially the one of the Dollar concert.

“We had the dome set up down in the fields, which we later shifted and put it up near the creek, when we stayed after the festival. We put it at the creek at the back of the shops, you know that area down there? It was the swimming hole.” [30]

Jonny Lewis comments:

“In retrospect probably it's slightly embarrassing, all these hippies, of which I was one. [As]were we all? And I remember Dollar Brand playing. That endless music was just extraordinary. I remember the Mornington Island Dancers because I had a little bit to do with them post Nimbin, and I remember, of course, Philip Petit. I was there when he rode into town on his unicycle. He was up for anything, that guy and I find him one of the great extraordinary poets ever. What a thing to do. I think I've been blessed in many ways and I'm very lucky. But you gotta take a few chances for this to happen and you can't be too humble about it because sometimes it's very hard to know what you're meant to do... Yeah, you had to be brave to be different and I think that that's something we don't see too much of. Maybe it's been refined a little bit too much.” [31]

The 'video energy centre' (as it was described in a note announcing it in Cantrills Filmnotes #13, p.31) was established by Mick Glasheen, Joseph El Khouri (Joe Correy), Melinda Brown, 'Fat Jack' Jacobsen, John Kirk, Jonny Lewis and Anne Kelly with contributions from Roger Foley, Martin Fabinyi, John Voce, Doug Richardson and others from Sydney and Robin Laurie, John Hansen, Ian Batty, and others from Melbourne, as well as David Tolley from Adelaide and Steve Jodrell from Perth.[32]

In the Filmnotes piece Joseph El Khouri said:

“... we want to find out about the video resources available and the people in the country interested in video and connect them together at the Festival. We'll have a lot of equipment together at the one time, so it'll be an intensive experience with video.” [33]

So they made their way to Nimbin over the weeks before the festival. Glasheen had a geodesic dome, for which the new skin was acquired, and it was set up as living quarters at Nimbin. BV arrived in the van one or two days into the festival. The video distribution hub was established in a house near the centre of town, and the work of laying the coaxial cable network began. They didn't know how to do it and Fat Jack had to teach people how to solder connectors and make the cables. The cable was passed along the rooftops up to the Rainbow Café, the pub, the Town Hall and buried down to the amphitheatre where the main stage was. [Check reference] Glasheen notes:

“I can remember laying all this coaxial cable down to the showground where the main stage of the festival was going to be. We thought we’d be broadcasting... or we’d be recording on the main stage and sending the picture back up to the studio up in town, like, a mile away, by this coaxial cable... and spending days putting in this coaxial cable, but it never happened.

“Well there didn’t seem to be anything on at the main stage to record because the festival itself was like, developing. It was an organic sort of thing. I mean no one knew what the program was going to be.” [34]

To which El Khouri adds:

“So we’re up at Nimbin with our equipment and we built all this cable. We were a bit naive about setting up a cable. We got it working, sort of. It was never as wonderful as we would have liked it to have been. But Fat Jack actually laid all this cable out in the – you can see on that plan [Fig.1] the ambition of it. We had video out through everywhere. We did get it going in the shop windows and stuff. And of course the PMG research department came up and saw it, and they were impressed that people were trying to do this. A guy called Hugh Guthrie.” [35]

John Kirk notes:

“I was doing more of a support thing [at Nimbin], because there was… A lot would happen, because Dr Karl Kruszelnicki and Mad Jack, and Fat Jack, and John Sisson were all up there building little Perspex pyramids with video distribution amplifiers in them. And modifying old TV sets, so they could use them as video monitors. Getting round the town and getting the whole thing wired. [36]

They were actually modifying the TV sets on the site in Nimbin.

Kirk again:

“On the spot, on site. And banging nails into telegraph poles and stringing cable round. And Fat Jack had made the archetypal aerial image lens, right, so we could pump 16 mm stuff into the gate of a video camera, and distribute that through the town. So that was like War of the Worlds, and other stuff. [37]

They were actually sending films out on that network as well. “And it was interesting, because people were up there from Swinburne with portapaks. Like Anna Soarez was there. [38]

Glasheen continues:

“But we knew that also the aim was to open the equipment up for people to use. The people that came to the festival could learn how to use the equipment and borrow it, take it out and record things, and that’s what happened. So a lot of people came in and took out equipment and recorded, brought it back and...

“But, I didn't record anything myself. I was fully occupied in setting the whole thing up, and putting in this coaxial cable … and then all these tapes came in, but we kept on not having enough tapes and recording over the tapes and not putting any value on what was recorded. Because when I was seeing it it didn’t look like it was all that valuable anyway. You know, much of it wasn’t well recorded.

“And when we came back from Nimbin there was always this kind of project to edit the Nimbin tapes, to get them down, to actually make them viewable, and there were a couple of edits, you know, there was the Bush Video to England edit that John Kirk did, and then a few other edits...

“So we were at Nimbin for about a month or so I suppose.” [39]

It took nearly the whole period of the festival to get the cable laid but it did happen and towards the end of the festival some of the videos that had been recorded during the festival were shown on the network. [40] However, during the festival the “video freaks” at the “video energy centre” were maintaining and lending out the portapaks to all comers and many tapes were shot.

Glasheen mentioned David Elphick's story of seeing the woman giving birth on the cable TV installed in the pub after about a week of snow on the screen while BV laid the cables and got the gear ready. The birth is said to have happened on the first night of the Festival [although according to Mac Gudgeon, the father, that is not the case] and had been recorded, but it was only once the cabling was finished and the distribution system installed in the Communications Centre that it became possible to get a playback out to the sites in the town where the TV monitors had been installed – including the pub, the Rainbow Cafe and other places. [41] Joseph notes:

“I had the birth tape. I didn’t shoot it, it was shot by a guy called Carey Court, I think, for Mac Gudgeon who became a scriptwriter. [It’s] his wife. I don’t think he knew I was doing all this. He’d lent me this tape. I later heard from someone else he hadn’t wanted to make it so public, however he never complained to me about it. But anyway. He was married to this girl – I knew him from the Shakahari. [42]

“And then the local Nimbin cop came and asked us: “Could I see that video?” So I went down to the policeman’s house and showed his wife who was about to have a baby. He must’ve heard about it because I gave him a private viewing. I mean, I’m not sorry that I did it. I do feel I should’ve probably – maybe if I’d informed Mac Gudgeon of it. It was a no-no. I didn’t think. I thought, you can do anything in this life, as I said. It was just so open.

“Well, I suppose it’s a bit of an affront, it’s a bit rude to the girl. But we thought it was so beautiful, so we were coming from that innocent pure place, and we certainly didn’t mean any disrespect. In fact, it was actually reverence.” [43]

[On Nimbin see the video by Roger Foley at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GWQMuKTNdzY]

In an interview for the ABC's GTK (Get To Know) with Jonny Lewis and “Fat Jack” Jacobsen, two members of the group that set up the Nimbin video centre, the interviewer asks Jonny Lewis: “You did a big video thing at Nimbin. Can you explain how that worked, and some of the things that happened from it?” to which Lewis replies:

“Oh, well. How did it work? Well we had all this equipment that we bought in the last three days before going up there and it was just an open access situation where anyone who was at the Nimbin Festival could come and borrow a portapak and generate their own video, their own information. Anything that they wanted to say they could say it with videotape.”

“It was really quite beautiful because of all the lightweight electronic gear we've got. We actually had people who had come to the festival to have fun, taking away just a little suitcase and a camera and going out and … shooting videotape the way they felt, coming back to us and we just had a terrific library of all the tapes that these people had shot. And then … how would you say … narrowcasting all this stuff down a cable into the town, [to television monitors set up] around the town, and people would be just standing there awestruck watching television that they'd made days before or maybe hours before. So it was a beautiful little community service thing that was made possible by the modern lightweight television stuff that's now available.” [44]

El Khouri made several tapes – including recordings of some of the main events by the international celebrities such as Dollar Brand (Abdullah Ibrahim) on the main stage and the Bauls of Bengal concert at the Town Hall, [45] Philip Petit's tight-rope walk across the main street at night with flaming torches, the Hare Krishnas, and then just what was happening around the streets, concerts, Paul Joseph had a parade. There were many other tapes shot, from play in the swimming-hole to street performers to trips into the surrounding countryside and whatever people thought interesting at any moment.

However, to a large extent the festival participants had little experience of film or video making, and as Glasheen noted, during the festival

“all these tapes came in, but we kept on not having enough tapes and recording over the tapes and not putting any value on what was recorded. Because when I was seeing it, it didn’t look like it was all that valuable anyway, you know. Much of it wasn’t well recorded.” [46]

Joseph noted:

“We probably stayed a few weeks. We shifted the dome down to the creek, and we were swimming in the creek, going out – and maybe there was talk of buying land, or something. But it probably hadn’t been bought yet, but we actually were involved with the exploration, and the guys who bought Tuntable Falls – Terry McGee, and another guy, they used to stay at Bush Video and we went out and made videos of the land before it had been purchased and that. Melinda actually bought a share for a few hundred dollars. And so during the festival, I shot quite a bit of video, filming people doing yoga and I’d just go off with the portapak, and probably Jonny shot stuff. Mick shot… and I did the Dollar Brand concert. There’s photos of me on the top of the van with the portapak, around the place, I think, in that collage of John Kirk’s in the Bush Video Tharunka. [47]

Nimbin as a model access centre

John Kirk has suggested that the Communications Centre at Nimbin became the first actual Australian experiment in setting up and operating a video access centre. [48] In effect, Bush Video at Nimbin was a model of an access centre and an attempt at a community TV centre. It provided the model or seeded the demand, the need, for the Film and TV Board to actually create the access centres. This all came about through Mick and Joseph's discussions with Johnny Allen.

While at Nimbin they had rented a house on the main street to set up a studio. It was really just the front room of the house and it was really just an equipment store with a maintenance bench. The portapaks were taken out and used to shoot whatever festival people wanted to record. The video was shot mostly not by BV people but all sorts of festival participants. People would come and borrow the equipment and take it out into the festival sites. BV basically taught people how to use the gear. Then the tapes were brought back and, when the cable set up was operating, played back on the cable to the monitors sited around the town.

[Check for a reference]

Others who were involved in the Communications Centre at Nimbin and worked on film and video productions or other sociological and archival activities included Roger Foley who shot a film of the day -to-day activity of people at Nimbin during the festival; Benny Zable who, much later, worked with people from the Woodstock museum on a doco about Nimbin, for which Mick did an interview. Anna [Ana?] Soares a Portuguese student at Swinburne Film & TV course Melbourne was involved and shot some video. Sri Richard was the source of the mandala's (used in the computer graphic tape) which were originally watercolour paintings. He was following a current of yoga practice which was also very much a part of the BV thing at this stage and of which Joseph was a strong exponent – as were the long meditatiive feedback videos. [49]

“Jeune [Pritchard, who later became the director of Paddington Video Access Centre] was there too. She was doing a lot of video. Because I remember she might’ve had a portapak, and I helped her with it, charging the batteries or something.” [50]

Jeune Pritchard and her partner Megan McMurchy had brought a portapak to Nimbin with them. They also recorded around the festival and may have been involved in the GTK recording of the festival, because Jeune was working with the ABC as a producer for GTK.

There was also some good video of the Dollar Brand concert recorded [by Joseph] – the sound was good because they plugged the portapak into the PA [Check reference]

After the festival some of this band of artists, film-makers, architects and others became Bush Video. [They were Mick Glasheen, Joseph el Khourey, Melinda Brown, “Fat Jack” Jacobsen, John Kirk, Annie Kelly and Anna Soares. They were later joined by Ariel.] They returned to Sydney, moved back into the Fuetron building which became the Bush Video studio, while the members of the collective squatted in some derelict shops, also owned by John Bourke, on Glebe Point Rd. They then began to edit the Nimbin videotapes, but editing in those days was a very tedious affair and little was achieved. It was just about impossible to get a clean edit on the Shibaden ½-inch “bench” deck they used as a master recorder. [51] Despite the problems, if one persevered, a reasonable job of editing could be done [52] and John Kirk produced the Bush Video Tapes, a compile of the Nimbin recordings, that went to the UK with an Australian Film and Video Festival called …over to you which was held in London in April, 1975. [53]

Bush Video now saw itself as free to explore other aspects of video as a medium for communicating a more esoteric range of ideas through the synthesis of new realities: visual, architectural and sociological. This led to the making of lots of other video and, being back at Fuetron, the experimentation started.

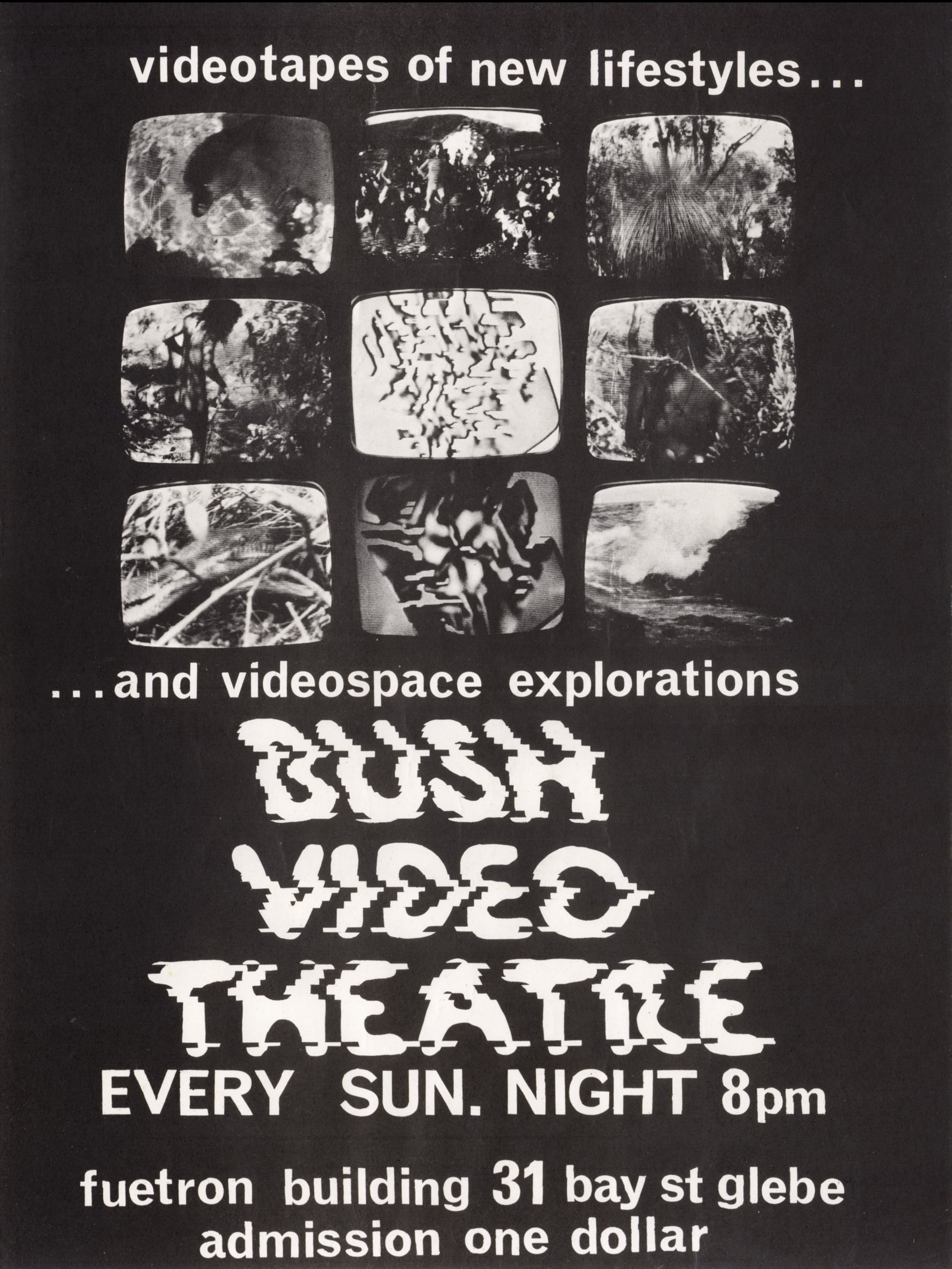

Bush Video was a loose collective of artists with a diverse range of interests who somehow managed to work together for nearly two years. The group had a constantly changing configuration but for those two years there was a strong enough connection for major events or projects to pull together those members needed for the task. They established a regular Bush Video Theatre [Fig.16] and the studio space in the Fuetron building became a gathering place for the group and their associates to try things out, discuss projects, gather collaborators and to show the results of the production to all and sundry. The primary video work was highly experimental with a considerable degree of feedback generated imagery, bits of computer animation, and Glasheen’s time-lapse footage, along with transferred films [54] and portapak video gathered from Nimbin and the city, and performances of dancers and musicians who joined in regularly. Bush Video was always inclusive.

Glasheen’s description of the attraction that video had for him illustrates the general underlying aesthetic that guided Bush Video in much of its work:

“I was drawn to the organic nature of it, [see Fig.4]… it seemed to me that video and electronic art is really an image of energy! It’s live light energy! Electromagnetic fields that are made visible! And so I was just attracted to that, to that... my God! This is amazing! That we’ve got our hands on this… that man (sic) can look at... Just like a television image. Like, the first time I saw a television image I couldn’t believe it. You know, there’s this glowing cathode tube with an image there that was alive. So I just felt that there’s life there, this new life-form, that could be felt - when you’re doing video effects, when you’re doing feedback, the feedback effect of video, Bush Video pursued hours and hours of this feedback... Then I was feeling drawn to that because it was this kind of… it seemed to be that that’s where the life was… in this machine. And what could be coaxed out of this? How could this be understood? What was this? And years and years later I kept on puzzling about what is this? What is the philosophy behind it? What is the scientific principle that’s going on here? I didn’t understand what it was at all.

“But now it seemed to come out that that is like a Mandelbrot set, in its kind of feedback formula. Like, this simple iterative process.” [55]

Bush Video was still affiliated with the AUS and in August published the Bush Video edition of Tharunka (the student newspaper of the University of NSW) which was intended to introduce the many facets of video to the students at UNSW, and to be more widely distributed to artists and community activists who might be interested in using video. [56]

“The Bush Video Tharunka happened after we’d come back from Nimbin. This was something we did two or three months after that [while] we were still part of AUS. This was a University of NSW publication... we were still in touch with the university to actually bring out the uni paper as a whole Bush Video edition. [57]

It summed up much of the general politico-aesthetic thinking of the time, not so much for the “fine art” world as for the “experimental art” world; the world of the hippies and the techno-freaks of the day, whose interests were largely the expression of an ideology of transcendence and the recognition of the ecological linkage between the world of nature and the development of the community both environmentally and spiritually. [58]

The diverse interests of the members of Bush Video, ranging from the practical to the artistic to the techno-mystical, can be seen in the content of the Bush Video Tharunka. It included:

There was a lot of psychedelic illustration in the Tharunka: Dick Weight did a lot of it while, as Glasheen notes:

“[the octopoidal Klein bottle] was Tom Barber’s drawing [Fig.9]. I find this is still really significant, this knotting of space, all this hyperspace that Tom developed with all his tensegrity. He built tensegrity structures which actually model these sorts of structures. Like knotting Klein bottles.

“So when we were doing this... we did this together, thinking: gee this would be great to have this thing going into a video space thing, but into that kind of topological space of intuitive formulations of video space topology. It says by Tom Barber. So I think it’s Tom, and I reworked it or something, yeah I was writing it and ... we were doing it together.” [66]

The Memory Theatre ideas came from Joseph.

“I was obsessed with these two areas of alchemy and memory theatre. Because I’d read this book of Frances Yates on Giordano Bruno and the art of memory. [67] I’d actually read that in Armidale. [68] I was reading Jung: Mysterium Coniunctionis. [69] So the feedback transforms your personal life. Cinema is a process of transformation, then moving into video, because it’s much more accessible and malleable to the personal. [I was] fascinated by the idea of memory theatre and Giordano Bruno and the idea that this is what the media was becoming, and would become, with the Internet later on, as it has become now, the universal memory thing. So I was trying to bring as much stuff … Alchemy as a Psychological process not with any idea of making gross metallic gold, what I was searching for was the perfect gold of a media induced sublime or enlightenment.” [70]

Having returned to Sydney new people became involved. [71] Joseph notes:

“Yeah, I remember [at the Fuetron building] there were different people would come there. There were bands there sometimes rehearsing. Paul Joseph, Sylvia and the Synthetics, I remember we videoed them, kind of a drag group. And then what we really wanted to do was start getting into doing abstract video, and play around with feedback and stuff. I remember first discovering feedback and thinking, Oh, this is great. I wanted to take it

further.

“As I said, we’d read about all these things [in Radical Software], and then when you actually do it, you think: This is really interesting.”[72]

Ariel had met Bush Video at Nimbin, and then joined in with Bush Video later in 1973. As Glasheen noted “he just arrived, a kid from school. He arrived maybe six months later...[MG: ???]

Ariel noted:

“but I wasn’t doing any video or anything at all then. I had actually just been a hippie at the time and I worked in electronics places before I lived in the bush, so I’d worked at George Brown’s and Davred or what ever it was called then [Radio Dispatch]. [They were suppliers of electronic] components.

“At the time electronics was an interesting place to be. I’d been interested in electronics first, and then when I met the people in Bush Video I just became very interested in the whole video thing. So when I came back to Sydney I went and saw them at Glebe and I just sort of fitted right in with what they were doing, and it just didn’t seem to take that long to start picking up all the stuff involved in doing it. Obviously I was lucky I already knew about electronics. [73]

I [the author] was drawn into Bush Video through the whole systems theory discussion. It was part of the Bucky Fuller thing. I remember walking up the stairs of the Fuetron building one evening with Tom Barber, talking about that sort of stuff, and suddenly realising that I actually understood all this stuff already. Because I’d studied systems theory at uni, over the previous years, ’71, ’72. And before I knew any of – well, I knew Mick by then and Albie Thoms by then, but I’d been doing Systems Theory when I was studying Psychology at ANU.

So the thing that made me think that made me realise that I was very much aligned to what was going on at Bush Video – was this discussion with Tom Barber about systems theory and the whole nature of systems and feedback structures and things like that. And the Bucky Fuller side of that, and so on.

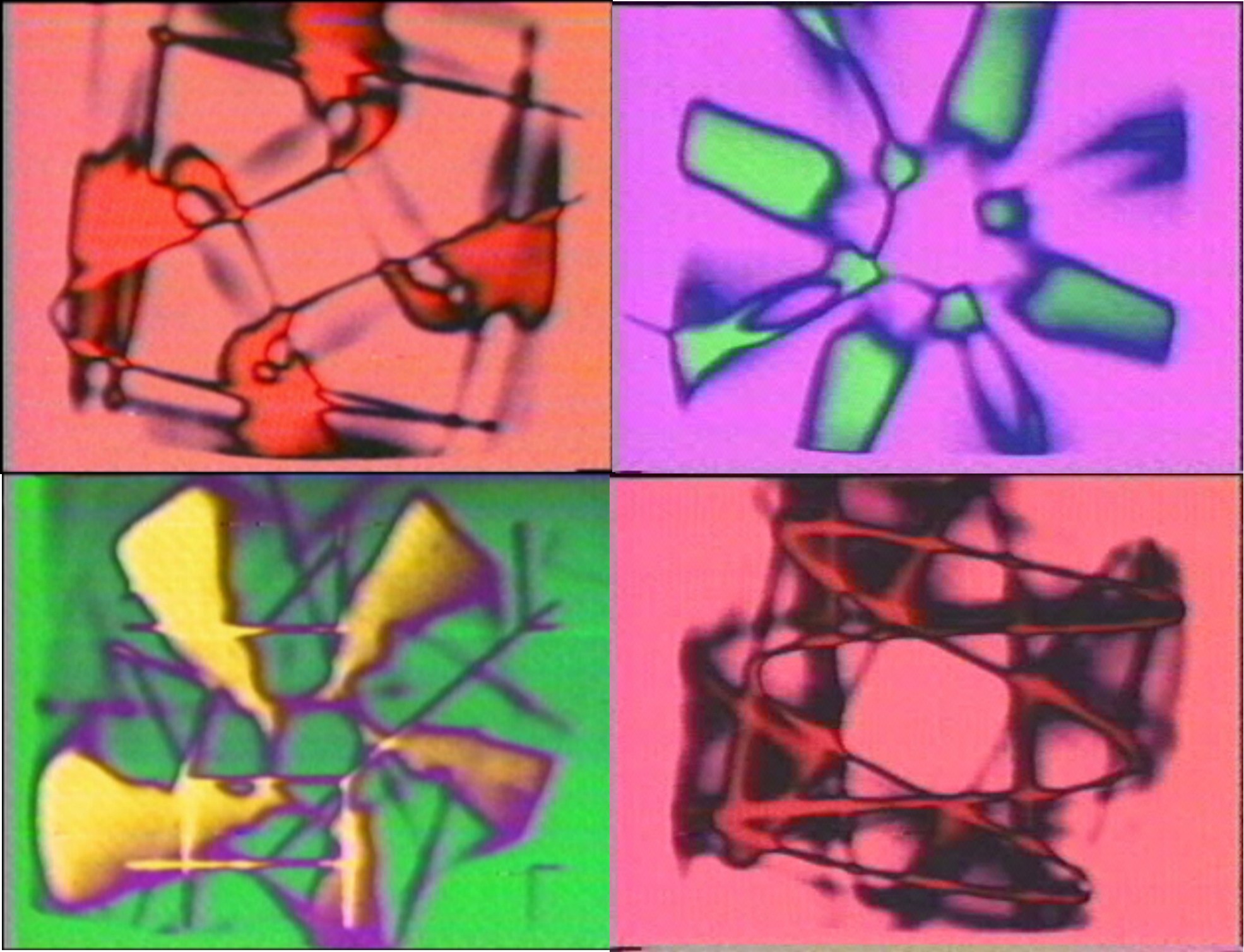

Having moved back into the Fuetron building Bush Video established a studio space in which a collection of video monitors was set up as a wall of screens, with the cameras in front of it for feedback or to record performances. Along the opposite wall was a “control-room” set up with the recorders and the mixer and whatever equipment they were able to build or borrow that could help make interesting electronic video. [74] [Fig.15]. One piece of equipment that made an irregular appearance was a video colouriser, known as a Cox Box [75], which was used to colourise the feedback effects that were so much a part of what Bush Video produced. Other equipment that appeared were an oscilloscope used for making Lissajous figures and later there was a video synthesiser built by Ariel, roughly based on the Rutt-Etra type of video synthesiser that was in use at Armstrong Audio/Video in Melbourne. [76]

As Ariel described it, much of Bush Video’s production involved

“remixing stuff that was captured with a camera. And [with] a lot of the stuff that we did, or I personally did, the mind boggling thing was where you’d have as many different sources as possible all being ... combined. One of the schemes was that you’d actually have all these banks of monitors sitting against the wall and then you’d have blank areas and there’d be like film being projected on parts of the wall. The whole place would be dark and … you’d be shooting the thing so it was like doing compositing with the camera plus mixing with more than one camera, and also colourising mono sources, and so forth.” [77]

Bush Video had a connection to Doug Richardson, who invited them to come and use his experimental graphics facility based on the DEC PDP-8 mini-computer, for which he had developed a PDP-8 based vector graphics application he called the Visual Piano. Graphic output was displayed on a large radar type screen known as the DEC Display 8 which had a resolution of 1024 x 1024 dots. The facility had originally been established through the collegial generosity of John Bennett, the then head of the University of Sydney Computer Science Department.

The system was used to produce a great variety of computer images that were used by several artists, including Gillian Haddley, Frank Eidlitz, other Computer Science students as well as Bush Video in several of their projects including Metavideo Programming, which we will come to below.

Both Glasheen and Ariel (while with Bush Video) used the PDP-8 to explore the sacred symbols of the tantra, particularly yantras and mandalas, drawing them in the computer, setting them to rotate and combine in various ways and then recording them with the portapak shooting directly from the 338 Display. Ariel also used the oscilloscope and his own version of the Rutt-Etra synthesiser and a lot of feedback.[78] You can see these in the videotapes I Know Nothing (1975) [Fig.5] and Escape from Paradise (1975) which were shown at Australia

'75.

John Kirk commented that:

“They were doing experimental things, like Ariel was fucking around with chips, right, with dividers, AND gates and all that sort of thing. And frequency splitting or something, and getting interesting stuff happening on screen.” [79]

In his presentation at my Synthetics symposium of 1998,[80] Ariel described his approach and the way electronic video was perceived at the time.

“all the other members were interested in electronically generated images but I think my particular speciality, if you like, was how to play around with generating images electronically. Also at the time there was this whole hippie thing going on and a lot of this type of material was seen as some form of electronic meditation. I guess this was made really before the video clip and music videos and what have you, so at that time it was just seen as visual music, as a kind of electronic screen-life that could be cultivated and farmed and what have you. At the time a lot of this stuff seemed to be much more mesmeric or something. Also we were emerging out of a very conservative period as well, so a lot of people at the time weren’t even cognisant of what it was, I mean, maybe they thought it was just that there were all these TV sets that were out of adjustment.”[81]

Creating interesting video feedback was one of the main things Bush Video explored, although many of the best feedbacks never got recorded. You had to set up the video and then finesse the system to do what you wanted to do.[82] Feedback is a decidedly evanescent process and the most beautiful effects can be lost by the slightest change of conditions, e.g., a change in the light level, a shift of the camera or trying to mix or key another video image into it. Also the 1/2”-inch recorder was somewhat unreliable and sometimes just getting it to start recording was enough to lose the effect. The thing about feedback is that it is a chaotic system and you are walking a knife-edge when producing it. However some tapes did get made.

The interest in Systems Theory, Bucky Fuller, video feedback and

“all the special effects was a way of communicating this consciousness of the world being like this organic organism, and every part connected. And to exploit this for the purposes of enlightenment and knowledge, expansion of knowledge, in the way that thinkers like Bucky was doing it and transforming it and coming up with inventions, and domes. And John Cage was saying there are no boundaries to music, and silence and reality is music and the sound that taps make is music, and mixing media was from phonographs and media and putting it all …. And of course then we discovered this metaphor of the effects mixer and the video processor, where you can make this a state of heightened consciousness where everything changes colour and reality becomes a malleable, transformable metamorphosing exhibition.” [83]

Glasheen continues:

“Then the video experimentation happened, with us looking at doing feedback experiments and then getting a commission from James Mollison of the National Gallery to do Metavideo Programming for the Philip Morris collection. And that enabled us to hire the video colouriser to do that. I remember James Mollison coming and seeing what it is we were doing... and approving, yes, this would fit into the Philip Morris funding to do an artwork that would be in an exhibition [and which] the National Gallery still have. And that would be a good video to get stills from because they've really got a compile of what we were doing. So Metaprogramming is really one of the only things to come out, or out of my side of it.” [84]

Glasheen’s Metavideo Programming [Fig.6] is perhaps the most important output from Bush Video in the Fuetron building. It was commissioned for the Philip Morris Arts Grant [85] by James Mollison, then director of the Australian National Gallery in Canberra. [86]

“And that enabled us to hire the colour video to do that. I remember James Mollison coming and seeing what it is we were doing... and approving, yes, this would fit into the Philip Morris funding to do an artwork that would be in a [collection] that the National Gallery still have. Meta-Programming is really one of the only things to come out, or out of my side of it.” [87]

Metavideo Programming was bought with funds provided by the Philip Morris Arts Grant, which was established in 1973 “to enable the purchase of works of art by “bold and innovative” artists for exhibition in State and Provincial galleries throughout Australia. … [It] has enabled people to realise projects more ambitious that they have attempted before; the statement from Bush

Video Group of Sydney was only completed in this form after an infusion of Philip Morris Arts Grant money.” [88]

The video was made using Richardson's PDP-8 computer graphics system. The geometric line drawn figures from his Visual Piano were recorded to Porta-pak video and then taken back to the Bush Video studio. There they were mixed with video feedback and colourised using a Michael Cox colouriser. The results were recorded to a Shibaden 620E half-inch VTR (a “bench deck”) and the playback from that was copied to U-matic video in 1975. That U-matic copy is what you can now see. The colour on the Shibaden was unfortunately never adequately stable but there is enough for you to see what Bush Video was trying to achieve.

Metavideo Programming consists in colourised video feedback driven by computer generated circles in a quadrilateral setting flowing out of the screen, each circle jumps from one position to a next position at 90deg to the previous. These are followed by three-to-one sine wave Lissajous figures, again generated on PDP8 with the feedback camera set to a slight rotational offset angle, so that the echo gives feedback. [Feedback is a product of constantly decaying and constantly refreshing echoes in an endless loop of light from monitor to camera to monitor and back to camera.] A sine-wave Lissajous image zooms in from centre to close up so only sections are seen, giving new kinds of feedback. Feedback then begins to be cut up by zooming the camera out to edges of monitor screen. Following this a new sequence of quadrilateral and pentagonal computer drawn geometric shapes: as lines, filled out by feedback, build up in layers of echoes. The quadrilaterals flow over each other giving multiple layers of rectangles and lines rotating about each other. Multitudes of these figures flow into a petal-shaped pentagonal feedback.

The highly saturated colours were produced with the 'Cox Box' colouriser. The whole is set to music by Tangerine Dream [Note: the music is copyright Tangerine Dream and no rights were obtained for its use. That was just not even thought about in the early 70s.]

Metavideo Programming was one of the final pieces produced by Bush Video although there were lots of experiments and test tapes. Later, after Bush Video broke up, other video pieces such as Escape From Paradise and I Know Nothing [Fig.9, above] were assembled, although they were made by Ariel and Joseph Khouri. It is likely that they were among the pieces finished at the Paddington Video Access Centre in 1976. Much of this post-Bush Video work was made during the period that I [the author] was volunteering with Paddington, particularly while the studio in the Paddington Town Hall was being built.

Having studied architecture, Glasheen had (and still has) a strong interest in the geometry of space, both architectural and microphysical. He had been visiting Richardson for a couple of years, doodling around on the PDP-8 system, drawing and animating 3D objects, especially the tetrahedron, a shape which has special significance, representing for him the fundamental geometry of the microcosm. He would then record them either to 16-mm film, before Bush Video, or to videotape during the Bush Video period. They often became incorporated in the mixdowns of electronic imaging that Bush Video specialised in, for example, the “circle and square and triangle, the old Taoist pattern” [89] that appears in Metavideo Programming.

As had Richardson, Glasheen found himself especially intrigued by the glowing trail the image left as a result of its persistence in the particular phosphor used in the screen of the 338 Display. While he and the author were looking at some of his film of the computer animations, he commented:

“It’s good seeing the old analogue screen isn’t it, eh? Beautiful line it makes, also ... seeing the persistence patterns, which you don’t get with the good digital computers... and that’s showing us the fourth dimension. It was like a computer game with the panel … so you could control the movement as it was moving though space, which was terrific. I also liked it when it breaks up like that, like it’s turning inside out or something. It’s [as though] the computer can’t control where its going, somehow you’ve zoomed it too far, but it’s a good effect.” [90]

One of the animations started as a 2D object spinning around and moving through 3D space [91] and grew into an animation of the flight of a boomerang intended for Glasheen’s film Uluru [92], [Fig.11]. As always there are bugs in experimental electronic systems and the PDP-8 was prone to them. One of the bugs was that with objects rotated about a centre there tended to be a line from that centre of rotation to the object as though it were on a fishing line. You can see this in the frames of the boomerang in Fig.1. Later in 1973, Richardson came over to the Bush Video studio and announced that he had the boomerang on the screen, so bring the camera. The boomerang was flying around the screen looping the loop and leaving the persistence trail “carving 3D space”, and it was finally running without the “fishing line tied to it”. [93]

Ariel also used the PDP-8 to explore sacred symbols that derive from Hindu yantras [94] and mandalas that are aids to meditation, drawing them into the computer, setting them to rotate, move and combine in various ways and then recording them with the portapak directly from the 338 Display. You can see these in the videotapes Yantras (1974 or 75?), I Know Nothing (1974) [Fig.8] and Escape from Paradise (1974), which in early forms were probably shown at Australia '75 in Canberra, although he also used an oscilloscope and his own version of the Rutt-Etra synthesiser and a lot of feedback. [95]

Ariel summed up Bush Video and the wider international community of video artists' understanding of electronic art as being part of a process of thinking about a new kind of language that would bring people into a new level of consciousness about their relations to the world and to the cosmos. For many of us we were orienting towards a new secular electronic notion of the divine.

“I guess it was more like an art rather than a science, … even though I think at the time, to do a lot of the stuff, you had to have some idea of how the technology worked or what was possible, or how you could possibly exploit certain potentials in it, or what have you. And I think that the visual medium, or the visual communication that Doug [mentioned at the Synthetics symposium (1988)] [96] will eventually come through but I don’t think that anybody has yet seen what that medium is. I don’t think that any of the particular technologies they make hint at what it could possibly be, and I don’t think that, currently, it exists or the germ of it exists per se. But I think that it will come through and I think there’ll be more and more of these technological obstacles giving way. I think that it will be easier for people, for programs or what have you to communicate any type of information.” [97]

It was this first generation of video artists, Australian and international, who read or were mentioned in the U.S. journal Radical Software, [98] who perused Guerilla Television [99] for its wealth of useful procedure with video, or who read and became engaged in (the then) new media through Gene Youngblood’s Expanded Cinema.[100] Radical Software was the main channel by which video activists and artists kept up with what was happening in all the burgeoning threads of video in the 70’s.

What arises here is the notion of video feedback as a simulation of, or perhaps a pointer to certain questions around the nature of consciousness. Much of this is brought out in Glasheen’s “Communication as a Conscious Experience of Energy” and el Khouri’s discussion of video as a memory theatre, both of which appeared in the Bush Video Tharunka. [101] Glasheen’s use of Richardson’s PDP-8 system was to make animations based on the intuitive sacred geometry [102] that he (Glasheen) felt was an important aspect of this new communication. Richardson was also motivated by this interest in completely new “physiologies” of communication that could be mined through both computer animation and video synthesis processes. As I have noted above video is a form of writing and this can be easily seen in the synthetic videos by Bush Video, as well as in the computer animations developed on Richardson’s PDP-8 calligraphic display.

But it wasn't just the esoteric in communications theory or in the mysteries. There was also considerable mention in the Tharunka issue about the community access activist kind of video work (e.g., the work of Tom Zubrycki or Warwick Robbins), and things that John Kirk was doing, and so on.

“That’s why we were a meeting of minds, and we, because, as I said, I could connect with that whole idea that Mick had gone into, because I’d already seen Bucky Fuller in the flesh. I was a total believer in that.

“And John Kirk and Martin Fabinyi were doing these things – we were very much aware of the whole religious thing, these kind of gurus and that. But I wasn’t really taken in by any of them as my own guru. We wanted to be our own gurus basically, not follow any gurus. But we were definitely influenced, well I was, by the whole Tantric thing.

“In fact, that Mookerjee book, from the fantastic library in Melbourne University union… They had everything. They had all the obscure stuff, and I knew some of the people. I knew this one poet that used to work in there behind the counter. And I’d go in there, listen to Zappa and stuff like that. That was another big influence. Bert and I were both Zappa freaks. I was so into music, but I didn’t have any income to buy all the latest records. So this was ideal. And Melinda used to go there too.” [103]

At the same time there was a great deal of interest in other forms of media for the making of art and for the diversification and democratisation of communications. One of the new developments was the instant photography enabled by the Polaroid SX-70. Within the photography world in Sydney, Jonny Lewis was one of the first to take up the potential of the SX-70. As he comments:

“The one thing with video, of course, was you could play it back and see it immediately, and you couldn't do that with film. I don't know what happened, but someone said, "Oh why don't you go over to Polaroid." And ironically Polaroid was adjacent to the Fuetron building. It was about two minutes walk, just off Bay Street, the first street on the right and it looked back towards Broadway. That was the office buildings of Polaroid. And I went in there the first day and introduced myself, and there was a fellow called Don Michaels, who was from America, and I walked out with an SX-70 and of course, then I became... Then I thought it was a great complement to have the SX-70 and the video. Although I was trying to learn as much as I could from the SX-70, it was very exciting because we had state-of-the-art technology, if you will.” [104]

This led Lewis to become the “house photographer” for Bush Video while it was at the Fuetron building. He took a lot of photographs within their space – of people, of each of them, from in the kitchen and in the studio and stuff [see Figs.14 & 15], and then he took a lot of photographs out in the bush and various places of social activity.

“I was just educating myself with it. I didn't really... I think probably in the early '80s I started to start processing and all that sort of thing. I think it had got me going with the SX-70, got me intrigued, and I was beginning to form some ideas. But as you say, you don't wanna think too much.

“I made very little [video there]. I remember long nights, very long nights, with Mick, just watching Mick mainly, doing feedback. And there was something about it that was completely compelling, and he would just be there tweaking it, and tweaking it, and tweaking it. And it seemed like it took forever. And of course, we were... All the accoutrements to that making of the particular feedback tapes were done mainly by Mick.

“John Kirk. He came around. I can't remember what he did, though. But, he was good. Joseph was around, though he didn't spend too much time with us, although he was obviously of leadership material. “Mick was the inspiration. I always have to say that, because he was just... He was great, he was into it. He was very... There's something very warm about him. He's warm and he's sincere and he's got a sense of humour. And the world's lucky for him and his movies.” [105]

John Kirk managed to edit a compile of the Nimbin material along with other Bush Video output into a tape he called Bush Video To England. He says of the process:

“Basically, in those days it was like start two machines and then press the button when the right picture went past, and you’d mark the tape, with a grease pencil and wind it back three marks and then start them.” [106]

Video as a form of writing

The computer-generated calligraphic mandalas and the oscilloscope waveforms and Lissajous figures are the main image sources that I am thinking about as being examples of this form of inscription. [107] The inscription in these instances may or may not have any semiotic referent to which it points. Obviously with much of the computer graphics, where the intention was to produce geometric images and mandalas these are clearly signifiers, though with the Lissajous figures, be they Ostoja-Kotkowski’s complex raster manipulations or Bush Video’s oscilloscope traces there is no such immediate signification. But when I look at them they remind me of the beautiful calligraphy of Arabic when it is applied to invocations of Allah [The One] or represents passages from the Koran. However, for modern video artists, these implications would not have been their main thought, though perhaps some saw that connection. For many in the underground, the main spiritual interest at the time was the Western view of the Hindus and their mandalas which are generally geometric and are used to represent states of mind, especially the clarity of emptiness that might be obtained through meditation and this returns us to the whole notion of video as a contemplative and perhaps consciousness expanding medium which appears in some writing about video and transcendence. [108] It is also worth remembering that the scan of the facsimile [see above] that lies at the basis of video was also seen as a means of transmitting both handwriting and Chinese ideographic characters.[109]

This non-representational video writing is basically formalist and determined by the technical capacities of the device generating the image. Thus the image is an abstraction of the formal properties of the device itself. Much music is made like this, for example Bach’s mathematical play with the semi-tones of the octaves available on various stringed instruments, and with counterpoint. Another example would be the possibilities inherent in electronic music, when it is not used for the programmatic composition one usually finds in film music. I have already mentioned the relation of synthetic video to electronic music, and this inscriptive video, coupled with video feedback, that Bush Video made is one example of that process.

Of the Bush Video work in this field of abstraction there are several examples. Video Meta-Programming (1973), [Fig.11] Escape from Reality (1974) and I Know Nothing (1974) [Fig.10]. The latter two were completed at City Video (otherwise known as the Paddington Video Access Centre) while Bush Video was based at Guriganya (see below) and were shown during the Bush Video presentations at the Computers and Electronics in the Arts exhibition at Australia 75 held in Canberra in March 1975 (see Chapter ?). These works are of the type that were generally considered contemplative, and clearly had psychedelic implications. They are long difficult and ultimately unsuccessful works produced through what amounted to improvisational processes, but they show moments of extraordinary beauty. They should probably be best categorised as “visual music”.

Bush Video Theatre

In terms of actual video activity the main context in which these sorts of ideas were exercised was in the regular Sunday night Bush Video Theatre events which were mostly situations in which anyone who was interested could come and hang out in the studio and engage in the video mixdown, musical improvisation and general conversation (not to mention quite of lot of pot smoking) that occurred during these evenings. As it was almost impossible to edit with the gear that Bush Video had, most of the recordings were done in long takes, which quite suited the improvisational approach.

Ariel describes:

“We had about 10 vcr’s and monitors all stacked in different ways and in a darkened space you could actually see all these separate tapes running at the same time so you could get a mix, if you like, in the viewing space of all these different computer and analog generated video sources. A lot of the mixes that we did [were] where we’d actually play back video on monitors in darkened rooms, project film onto the wall [of monitors] and then shoot the whole thing again with another camera, or sort of, like navigate around what was going on. So you could do a large mix by surfing with a camera all these different sources that are in a darkened space. We also relied heavily on various standard types of video equipment, special effects generators or mixers, colourisers and some weird, strange machines that were built.”

Losing Fuetron

Things started to become difficult for Bush Video at the end of 1973. Joseph comments:

“And then we started... we had a few battles, and funding was always a problem, with getting access to the equipment, hiring that colouriser, different things like that we wanted to do. And we had technical limitations. And then finally the place came apart when Johnny Bourke started to lose his – there must’ve been a recession or something some time.

“And he lost – because he was over[-extended] – he had all these properties. He had so many properties that I guess he only owned part of them, and he was owing so much. And his cash flow couldn’t keep up with it. And there was a recession, and he was called on these and he lost on most of his buildings, except the Fuetron. And we lost that, and then Bill Lucas offered us Guriganya.” [110]

The Futron building period came to an end. As Glasheen notes:

“at the beginning of ‘74. We got to the stage where we were too far behind in the rent, we couldn’t keep up with the rent, not that it was very much... and it got to the stage where we were being locked out of the building. There was no door on the building for most of the period, there was no front door. So anybody could walk in and walk out… So I was actually sleeping on the floor up there just to… you know so

someone was there, but there was never any problem.

“But, I remember we had to go in about mid-’74 and Bill Lucas had offered Guriganyah as a possible place … he was involved with this alternative school that had space that could accommodate us, and we could interact with the kids. So we moved there, to Guriganyah, in mid-’74. So we must have been there [at Fuetron] for a year, was it? So that would be about when you came in mid-’74, about the time we moved there.

“Then, I remember it was all a matter of keeping it going, really... and just enjoying life keeping it going.” [111]

One of the last projects at Fuetron was a collaboration with the architect Bill Lucas, who was proposing a very radical transformation of Woolloomooloo. Kirk describes it:

“Mick and I did a thing with Bill Lucas, who owned the building that Gurigunya was in [and to which Bush Video moved when the Fuetron building became unavailable]. Bill was an architect, and he wanted to do a thing by running aqueducts right through Woolloomooloo and floating concrete extrusions ...

I then asked Kirk if it was “Those pyramid buildings that he was wanting to build?

“JK: Yeah, kind of, but the thing was to reticulate the transport through the whole thing, in aerial canals, right, with concrete boats floating, with the same profile as the ditch, but sitting on sticks. And so we did a kind of a chroma keyed colour simulation of that, using I’m not sure whether it was models that Bill had built, [but] most of it was done with models and drawings and that sort of thing, you know.

“So that was kind of interesting, and at that stage, people had moved out from where we were based in Glebe, up the road to Guriganya. And I’d moved out, and I’m not sure whether I was working at Alexander Mackie Art School at the Rocks at that stage. There was a big cross-over thing there, yeah.” [112]